Biological contamination is the dread of every person working with cell culture. When cultures become infected with microorganisms, or cross-contaminated by foreign cells, these cultures usually must be destroyed. Since the sources of culture contamination are ubiquitous as well as difficult to identify and eliminate, no cell culture laboratory remains unaffected by this concern. With the continuing increase in the use of cell culture for biological research, vaccine production, and production of therapeutic proteins for personalized medicine and emerging regenerative medicine applications, culture contamination remains a highly important issue.

Introduction

Cell culture is continuing a 60-year trend of increasing use and importance in academic research, therapeutic medicine, and drug discovery, accompanied by an amplified economic impact.1,2 New therapies, vaccines, and drugs, as well as regenerated and synthetic organs, will increasingly come from cultured mammalian cells. With greater usage and proficiency of cell culture techniques comes a better understanding of the perils and problems associated with cell culture contamination. In the 21st century, there are better testing methods and preventive tools, and an awareness of the risk and effects of contamination requires that cell culturists remain vigilant; undetected contamination can have widespread downstream effects.

Biological contamination: a common companion

Carolyn Kay Lincoln and Michael Gabridge summed up the contamination problem in 1998 as: “Cell culture contamination continues to be a major problem at the basic research bench as well as for bioproduct manufacturers. Contamination is what truly endangers the use of cell cultures as reliable reagents and tools.”

The biological contamination of mammalian cell cultures is more common than you might think. Statistics reported in the mid-1990s show that between 11 percent and 15 percent of cultures in U.S laboratories were infected with Mycoplasma species. Even with better recognition of the problem and more stringent testing of commercially prepared reagents and media, the incidence of mycoplasma growth in research laboratory cultures was 23 percent in one recent study, and in 2010 an astonishing 8.45 percent of cultures commercially tested from biopharmaceutical sources were contaminated with fungi and bacteria, including mycoplasma.

In the research laboratory, contamination is not just an occasional irritation, but it can cost valuable resources including time and money. Ultimately, contamination can affect the credibility of a research group or particular scientist; publications sometimes must be withdrawn due to fears about retrospective sample contamination or reported results that turn out to be artifacts. In biopharmaceutical manufacturing, contamination can have an even more dramatic effect when entire production runs must be discarded. It is extremely important, therefore, to understand how sample contamination can occur and what methods are available to limit and, ultimately, prevent it.

What causes biological contamination?

Poor Aseptic technique is the number 1 cause of cell culture contamination

Biological contaminants can be divided into two subgroups depending on the ease of detecting them in cultures, with the easiest being most bacteria and fungi. Those that are more difficult to detect, and thus present potentially more serious problems, include Mycoplasmas, viruses, and cross-contamination by other mammalian cells.

Bacteria and fungi

Bacteria and fungi, including molds and yeasts, are ubiquitous in the environment and are able to quickly colonize and flourish in the rich cell culture milieu. Their small size and fast growth rates make these microbes the most commonly encountered cell culture contaminants. In the absence of antibiotics, bacteria can usually be detected in a culture within a few days of contamination, either by microscopic observation or by their direct effects on the culture (pH shifts, turbidity, and cell death). Yeasts generally cause the growth medium to become very cloudy or turbid, whereas molds will produce branched mycelium, which eventually appear as furry clumps floating in the medium.

Mycoplasmas

Mycoplasmas are certainly the most serious and widespread of all the biological contaminants, due to their low detection rates and their effect on mammalian cells. Although mycoplasmas are technically bacteria, they possess certain characteristics that make them unique. They are much smaller than most bacteria (0.15 to 0.3 μm), so they can grow to very high densities without any visible signs. They also lack a cell wall, and that, combined with their small size, means that they can sometimes slip through the pores of filter membranes used in sterilization. Since the most common antibiotics target bacterial cell walls, mycoplasmas are resistant.

Mycoplasmas are extremely detrimental to any cell culture: they affect the host cells’ metabolism and morphology, cause chromosomal aberrations and damage, and can provoke cytopathic responses, rendering any data from contaminated cultures unreliable. In Europe, mycoplasma contamination levels have been found to be extremely high—between 25 percent and 40 percent—and reported rates in Japan have been as high as 80 percent.4 The discrepancy between the U.S. and the rest of the world is likely due to the use of testing programs. Statistics show that laboratories that routinely test for mycoplasma contamination have much lower incidence; once detected, contamination can be contained and eliminated. Testing for mycoplasma should be performed at least once per month, and there is a wide range of commercially available kits. The only way to ensure detection of species is to use at least two different testing methods, such as DAPI staining and PCR.5

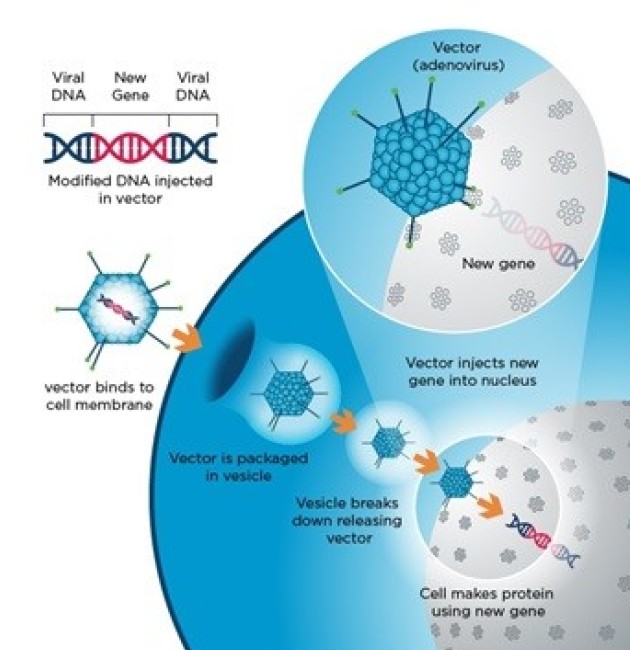

Viruses

Like mycoplasmas, viruses do not provide visual cues to their presence; they do not change the pH of the culture medium or result in turbidity. Since viruses use their host for replication, drugs used to block viruses can also be highly toxic for the cells being cultured. Viruses that cause damage to the host cell do, however, tend to be self-limiting, so the major concern for viral contamination is their potential for infecting laboratory personnel. Those working with human or other primate cells must use extra safety precautions.

Other mammalian cell types

Cross-contamination of a cell culture with other cell types is a serious problem that has only recently been considered alarming.7,8 An estimated 15 percent to 20 percent of cell lines currently in use are misidentified9,10, a problem that began with the first human cell line, HeLa, an unusually aggressive cervical adenocarcinoma isolated from Henrietta Lacks in 1952. HeLa cells are so aggressive that, once accidentally introduced into a culture, they quickly overgrow the original cells. But the problem is not limited to HeLa; there are many examples of cell lines that are characterized as endothelial cells or prostate cancer cells but are actually bladder cancer cells, and characterized as breast cancer cells but are in fact ovarian cancer cells. In these cases, the problem occurs when the foreign cell type is better adapted to the culture conditions, and thus replaces the original cells in the culture. Such contamination clearly poses a problem for the quality of research produced, and the use of cultures containing the wrong cell types can lead to retraction of published results.

Sources of biological contaminants in the lab

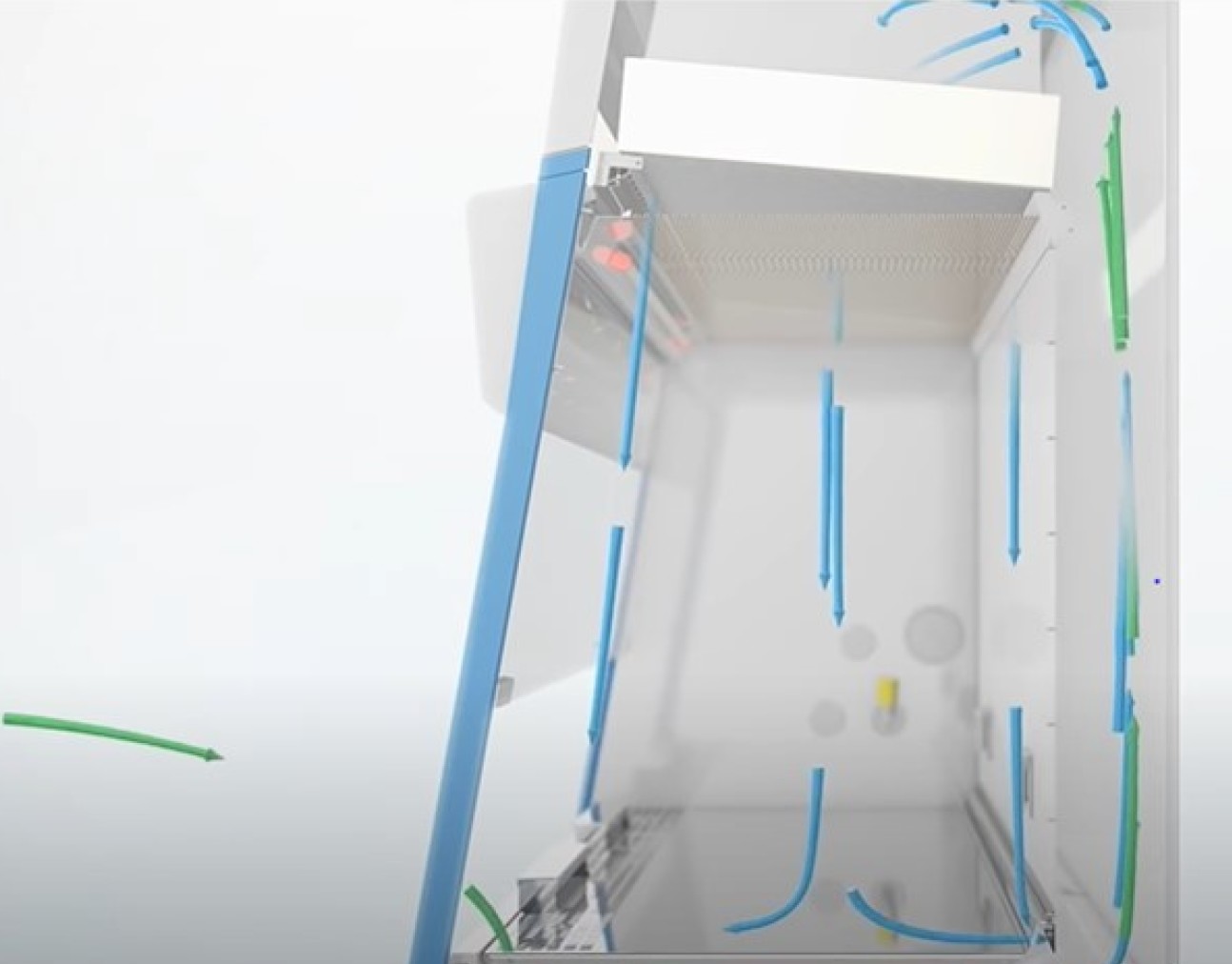

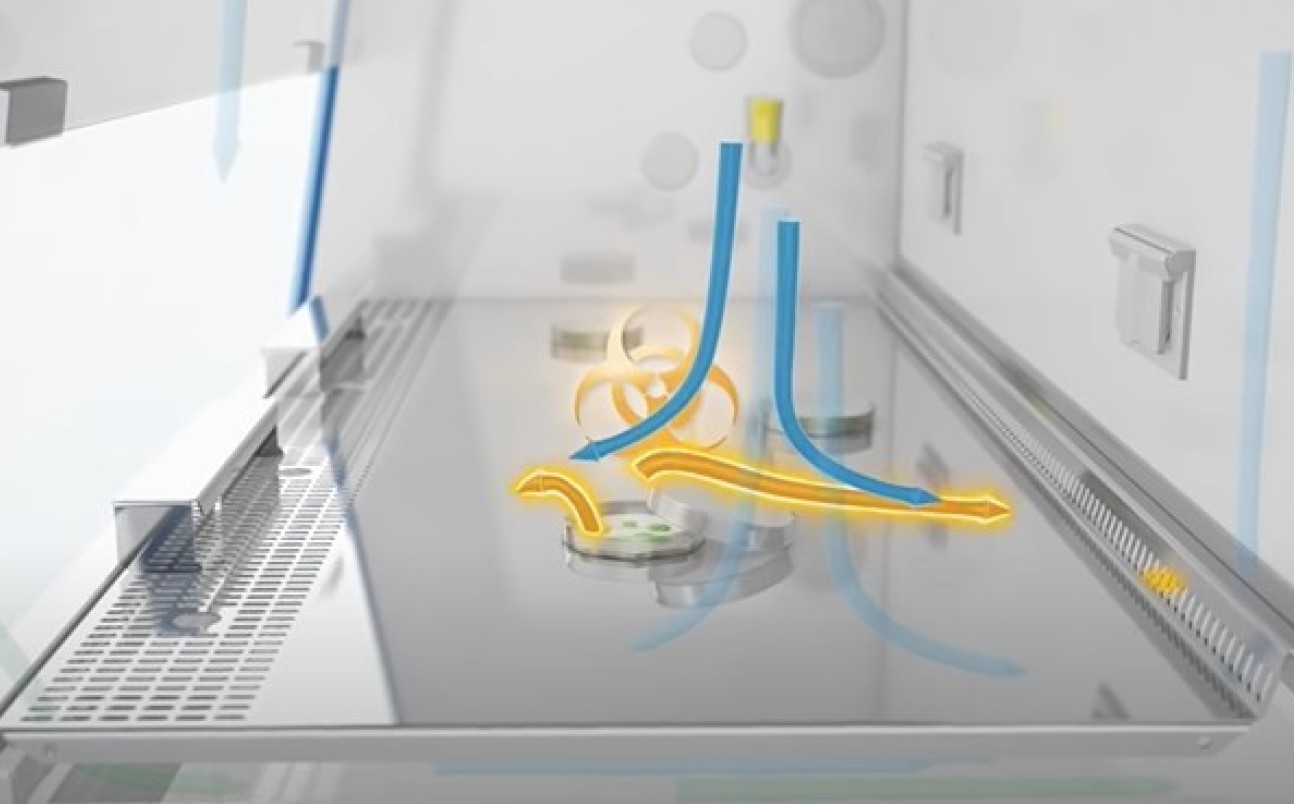

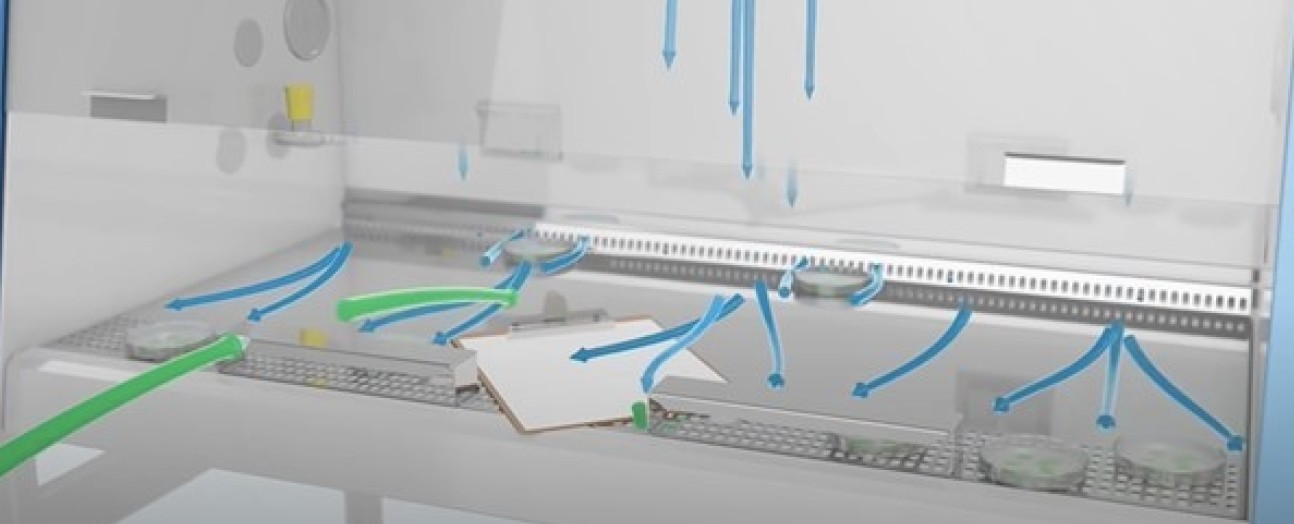

In order to reduce the frequency of biological contamination, it is important to understand how biological contaminants can enter culture dishes. In most laboratories, the greatest sources of microbes are those that accompany laboratory personnel. These are circulated as airborne particles and aerosols during normal lab work. Talking, sneezing, and coughing can generate significant amounts of aerosols. Clothing can also harbor and transport a range of microorganisms from outside the lab, so it is crucial to wear lab coats when working in the cell culture lab. Even simply moving around the lab can create air movement, so the room must be cleaned often to reduce dust particles.

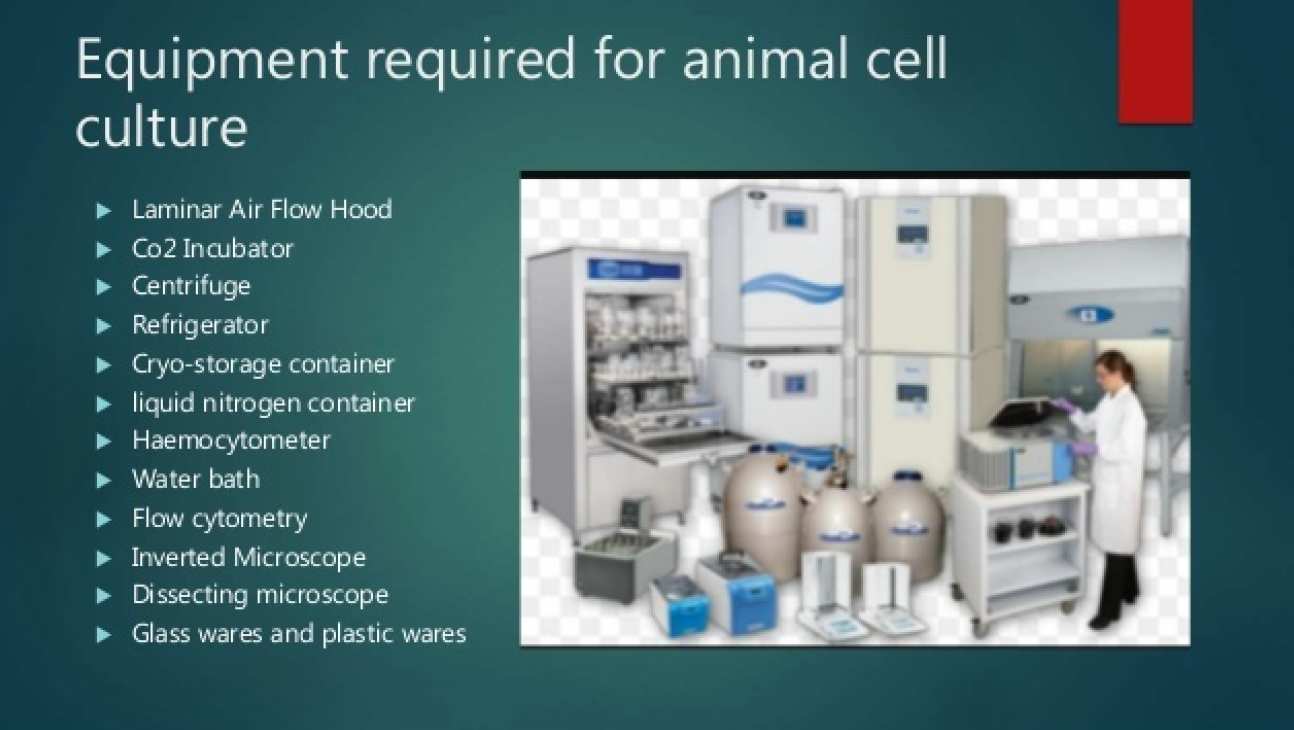

Certain laboratory equipment, such as pipetting devices, vortexers, or centrifuges without biocontainment vessels, can generate large amounts of microbial-laden particulates and aerosols. Frequently used laboratory equipment, including water baths, refrigerators, microscopes, and cold storage rooms, are also reservoirs for microbes and fungi. Improperly cleaned and maintained incubators can serve as an acceptable home for fungi and bacteria. Overcrowding of materials in the autoclave during sterilization can also result in incomplete elimination of microbes.

Culture media, bovine sera, reagents, and plasticware can also be major sources of biological contaminants. While commercial testing methods are much improved over those of earlier decades, it is paramount to use materials that are certified for cell culture use. Cross-contamination can occur when working with multiple cell lines at the same time. Each cell type should have its own solutions and supplies and should be manipulated separately from other cells. Unintentional use of nonsterile supplies, media, or solutions during routine cell culture procedures is the major source of microbial spread.

Conclusion

Contamination is a prevalent issue in the culturing of cells, and it is essential that any risks are managed effectively so that experiment integrity is maintained. Antibiotics can be used for a few weeks to ensure resolution of a known microbial contamination; however, routine use should be avoided. Regular inclusion of antibiotics not only selects for resistant organisms, but also masks any low-level infection and habitual mistakes in aseptic technique.

The best approach to fighting contamination is for each person to keep records of all cell culture work including each passage, general cell appearance, and manipulations including feeding, splitting, and counting of cells. If contamination does occur, make a note of the characteristics and the time and date. In this way, any contamination can be pinpointed at the time it occurs and improvements can be made to aseptic techniques or lab protocols. In the next article of this series, we explore in more detail effective measures for contamination prevention, in particular the key role of the CO2 incubator.

Class II Facility

Class II Facility

Dr Miguel Hermida

Dr Miguel Hermida