The Ulysses Spacecraft

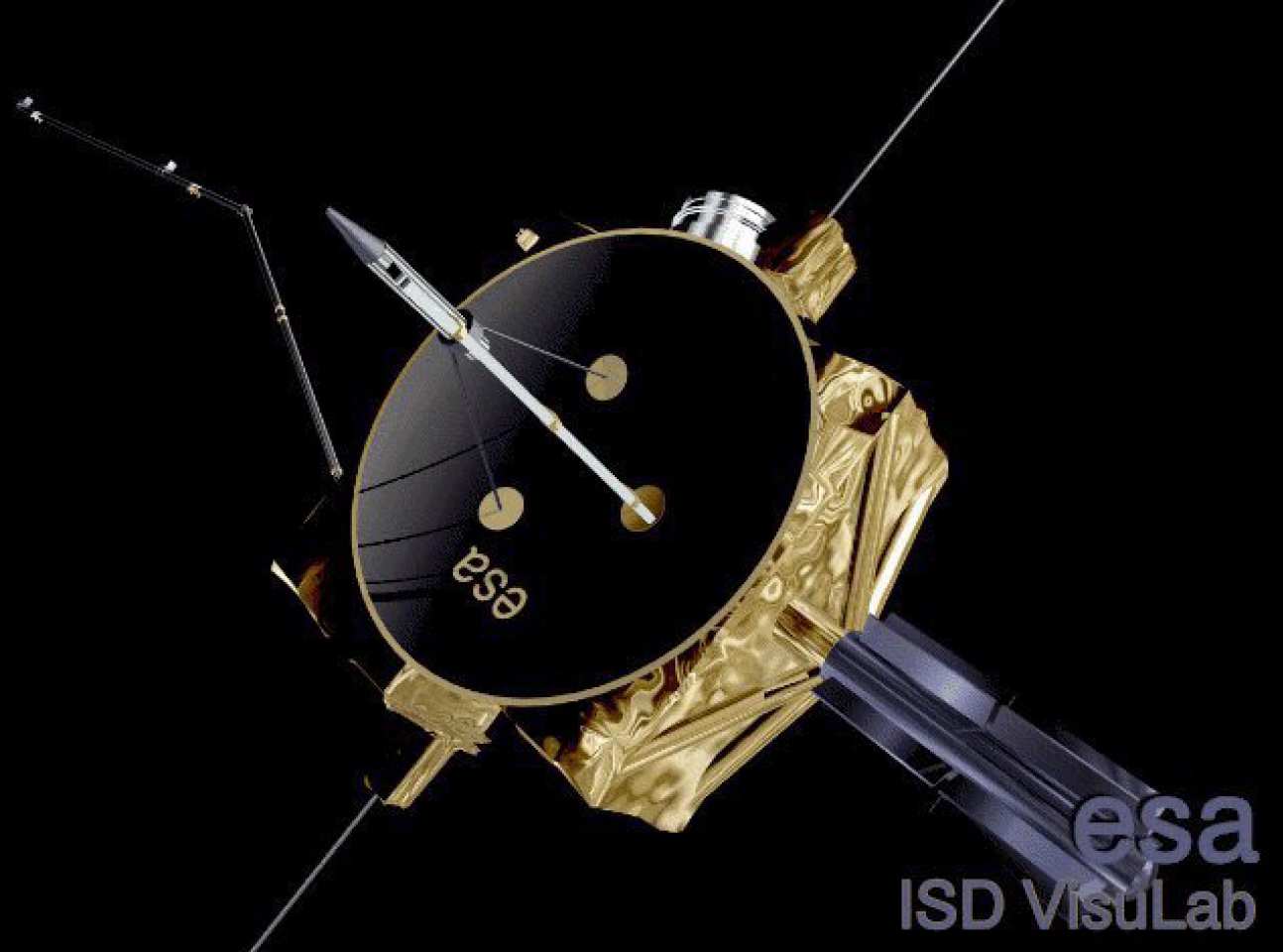

Ulysses is a joint ESA-NASA mission. The spacecraft was launched in October 1990, and carries several scientific instruments, most of which are designed to study the state of the solar wind as it flows past the spacecraft. The initial part of the mission (to February 1992) involved a cruise to Jupiter. The close approach to that planet then changed Ulysses' orbit drastically, putting it in an orbit which carries it over the poles of the Sun. This allows the spacecraft to measure the solar wind flowing from very high solar latitudes, which had not been achieved previously. Consequently, we have learnt (and are still learning) a great deal about the behaviour of the solar wind flowing from all over the Sun.

Ulysses is a joint ESA-NASA mission. The spacecraft was launched in October 1990, and carries several scientific instruments, most of which are designed to study the state of the solar wind as it flows past the spacecraft. The initial part of the mission (to February 1992) involved a cruise to Jupiter. The close approach to that planet then changed Ulysses' orbit drastically, putting it in an orbit which carries it over the poles of the Sun. This allows the spacecraft to measure the solar wind flowing from very high solar latitudes, which had not been achieved previously. Consequently, we have learnt (and are still learning) a great deal about the behaviour of the solar wind flowing from all over the Sun.

Science

The Space and Atmospheric Physics Group at Imperial College has interests in two instruments on Ulysses: the magnetic field experiment and the Anisotropy Telescope. This site has information about both instruments.

Imperial College London is the home of the Ulysses magnetic field and anisotropy telescope investigations.

Imperial College London is the home of the Ulysses magnetic field and anisotropy telescope investigations.

The Ulysses Spacecraft has, for the first time, explored conditions over the pole of the Sun.

Ulysses work at Imperial College London was funded by the UK Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council.

Ulysses, a journey from 1990 to 2009

The journey of the hero Ulysses happened perhaps three or more millennia ago. In May 2008, a group of scientists gathered in Kefalonia (that probably was the antique Ithaca) to celebrate the coming end of the Ulysses space mission, following an odyssey of a different nature, no less adventurous, around the Sun. Since its launch in October 1990, the spacecraft Ulysses has travelled more that 8,600,000,000 km (or almost 5,400,000,000 miles), rather more than the intrepid traveller in classic times.

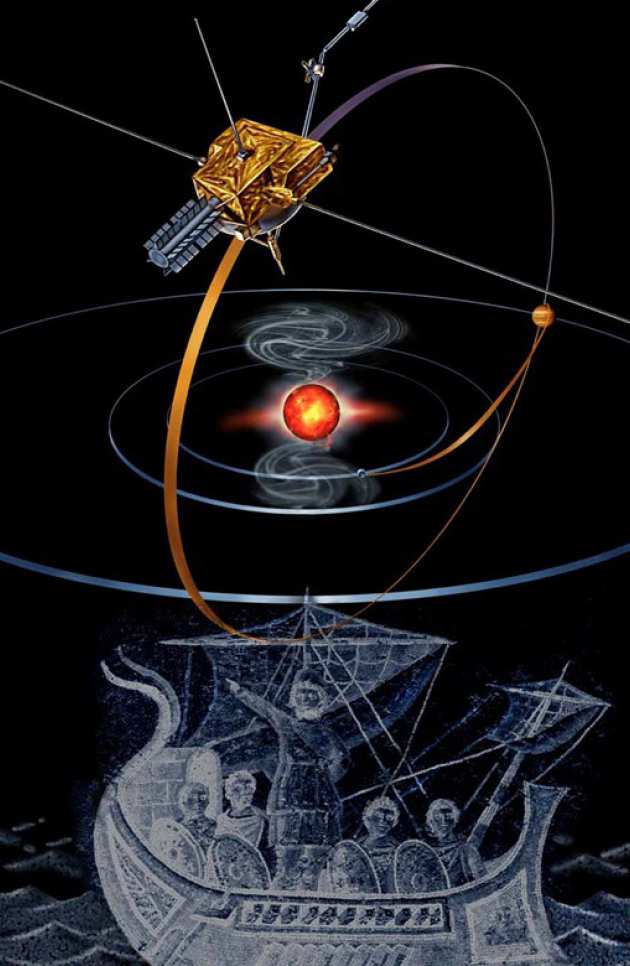

Image right: A hero who has travelled far and wide

The hero of the Odysseus, Ulysses, travelled far and wide in classical times, and after many adventures, arrived back to Ithaca, in the blue seas of the Adriatic off mainland Greece.

Ulysses, a journey from 1990 to 2009

- Imperial College involvement in this joint ESA-NASA mission

- Ulysses and the magnetic field

- Ulysses discoveries

- Still making discoveries, 18 years on

- Ulysses spacecraft surviving into 2009

- Last note: Ulysses mission terminated in June 2009

Imperial College was well represented at the scientific workshop on Kefalonia, the Space and Atmospheric Physics group in the Physics Department having played a leading role in this space mission since its start in the mid-1970s. The group has led the international team that built the instrument to measure magnetic fields onboard Ulysses, as well as an instrument to measure energetic atomic particles coming from solar flares. The whole space mission has been a joint undertaking between the European Space Agency, ESA and NASA; the spacecraft was built in Europe but it was launched onboard the Space Shuttle Discovery. It has been tracked by the giant dish antennas of NASA’s Deep Space Network, and operated remotely by a European led team of engineers.

The objective of the Ulysses mission has been to explore the heliosphere, the space around the Sun, for the first time in three dimensions. The solar wind (a constant flow of atomic particles from the Sun at speeds up to 1000 km/sec) fills the heliosphere; it also carries with it into space the magnetic field of the Sun. The magnetic field lines that permeate the heliospheric medium shape the structure of the heliosphere. All previous space missions only explored the heliosphere in a narrow band around the solar equator; Ulysses was launched towards Jupiter to get a mighty gravitational kick from the giant planet to eject it from that plane into an orbit around the poles of the Sun.

Following its encounter with Jupiter in February 1992, the orbit of Ulysses has been an ellipse, almost over the poles of the Sun. At its furthest from the Sun, Ulysses is at about 790,000,000 km from the Sun, and even at its closest, it remains at almost 200,000,000 km from it.

Present and past members of Imperial College gathering in Kefalonia (Ithaca) to celebrate the achievements of the Ulysses mission. From left to right: Dr. Tim Horbury, (PhD Ulysses), Reader in Space Physics, Dr. Adam Rees, (PhD Ulysses), Research Associate, Ulysses, 2003-2008, Dr. Richard Marsden (PhD, Imperial College 1976), ESA Project Manager, Ulysses, Professor Andre Balogh, Imperial College, Principal Investigator of the magnetic field experiment on Ulysses, Dr. Bob Forsyth, Reader in Space Physics, Neel Savani (PG Student, Ulysses), Dr Silvia Dalla, Research Associate, Ulysses 1998-2003

Present and past members of Imperial College gathering in Kefalonia (Ithaca) to celebrate the achievements of the Ulysses mission. From left to right: Dr. Tim Horbury, (PhD Ulysses), Reader in Space Physics, Dr. Adam Rees, (PhD Ulysses), Research Associate, Ulysses, 2003-2008, Dr. Richard Marsden (PhD, Imperial College 1976), ESA Project Manager, Ulysses, Professor Andre Balogh, Imperial College, Principal Investigator of the magnetic field experiment on Ulysses, Dr. Bob Forsyth, Reader in Space Physics, Neel Savani (PG Student, Ulysses), Dr Silvia Dalla, Research Associate, Ulysses 1998-2003

It would be too long to enumerate the discoveries of Ulysses. They relate to the many ways in which the solar wind is divided into two distinct kinds: fast and slow streams coming from different regions of the solar corona that change dramatically over the 11-year solar activity (http://solarscience.msfc.nasa.gov/). Solar activity is measured by the periodic increase in the number of sunspots on the Sun and its different consequences that include vast cosmic storms originating on the Sun and that also affect the Earth’s environment. From the Imperial College team and their collaborators in the United States and Europe there have been many scientific publications describing the heliospheric magnetic field, its structure, the large-and small scale changes that originate in the Sun’s corona and the turbulence that is developed as the magnetic field is dragged away from the Sun.

It would be too long to enumerate the discoveries of Ulysses. They relate to the many ways in which the solar wind is divided into two distinct kinds: fast and slow streams coming from different regions of the solar corona that change dramatically over the 11-year solar activity (http://solarscience.msfc.nasa.gov/). Solar activity is measured by the periodic increase in the number of sunspots on the Sun and its different consequences that include vast cosmic storms originating on the Sun and that also affect the Earth’s environment. From the Imperial College team and their collaborators in the United States and Europe there have been many scientific publications describing the heliospheric magnetic field, its structure, the large-and small scale changes that originate in the Sun’s corona and the turbulence that is developed as the magnetic field is dragged away from the Sun.

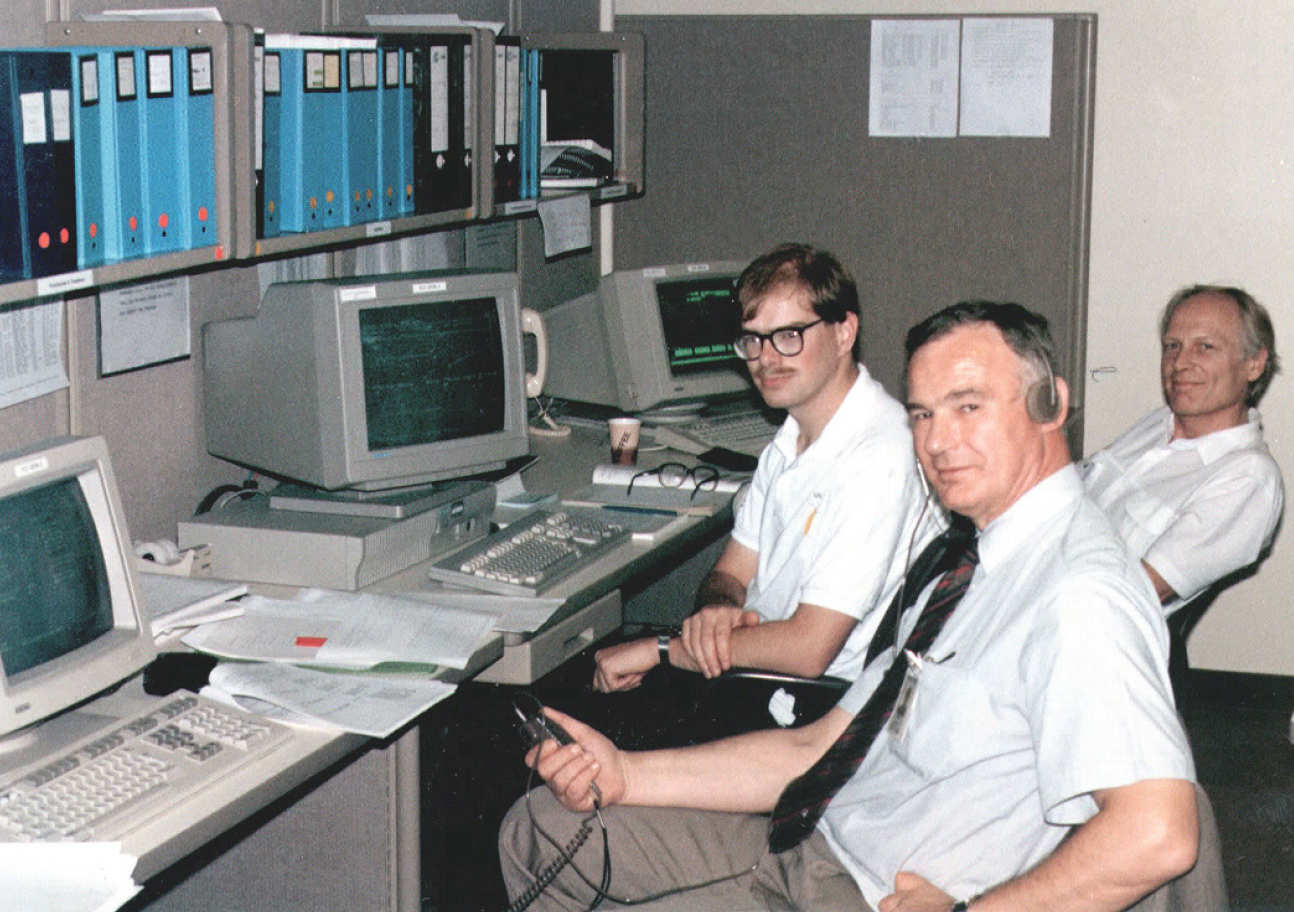

However, after 18 years in orbit around the Sun, the Ulysses probe is approaching the end of its life. The power source that it carries, the Radioactive Thermoelectric Generator, has decayed as all radioactive devices do, so that there is no longer enough power for all the spacecraft systems and the scientific instruments to function as before. Also, in an attempt to make more power available on board the spacecraft, the high gain amplifier that assured the broadband link with the Earth failed in January, so that it is only through a slow rate data link that the spacecraft can transmit its data to NASA’s largest, 70 m dishes. The spacecraft is also moving away from the Sun in its orbit, towards colder regions, and the lack of electrical power means that the fuel that is needed to keep it pointing to the Earth is about to freeze. We are witnessing the last weeks of a great space mission, it is thanks to the genius of the spacecraft operators and to the resilience of the spacecraft itself that it may be possible to last long enough to encounter the expected boundary between the slow and fast solar wind. Image shows the Imperial College team at Ulysses magnetometer switch on, October 1990

Recent results from the observations of Ulysses are quite dramatic: suddenly the Sun is not emitting solar wind as we have got used to it since the start of the space age 50 years ago. All kinds of questions are being asked about wh at wi ll happen to solar activity; there is indirect evidence from 300 years ago, that when the Sun’s activity was suspended, severe climatic events followed on the Earth: in fact a mini-ice age, with fairs and dancing on the frozen Thames, is well documented. Ulysses has intriguingly lasted long enough to bring us to the threshold of seeing maybe a repeat of the conditions all those years ago. We know, from many sources including the Ulysses space probe that the Sun matters a lot in our lives.

Recent results from the observations of Ulysses are quite dramatic: suddenly the Sun is not emitting solar wind as we have got used to it since the start of the space age 50 years ago. All kinds of questions are being asked about wh at wi ll happen to solar activity; there is indirect evidence from 300 years ago, that when the Sun’s activity was suspended, severe climatic events followed on the Earth: in fact a mini-ice age, with fairs and dancing on the frozen Thames, is well documented. Ulysses has intriguingly lasted long enough to bring us to the threshold of seeing maybe a repeat of the conditions all those years ago. We know, from many sources including the Ulysses space probe that the Sun matters a lot in our lives.

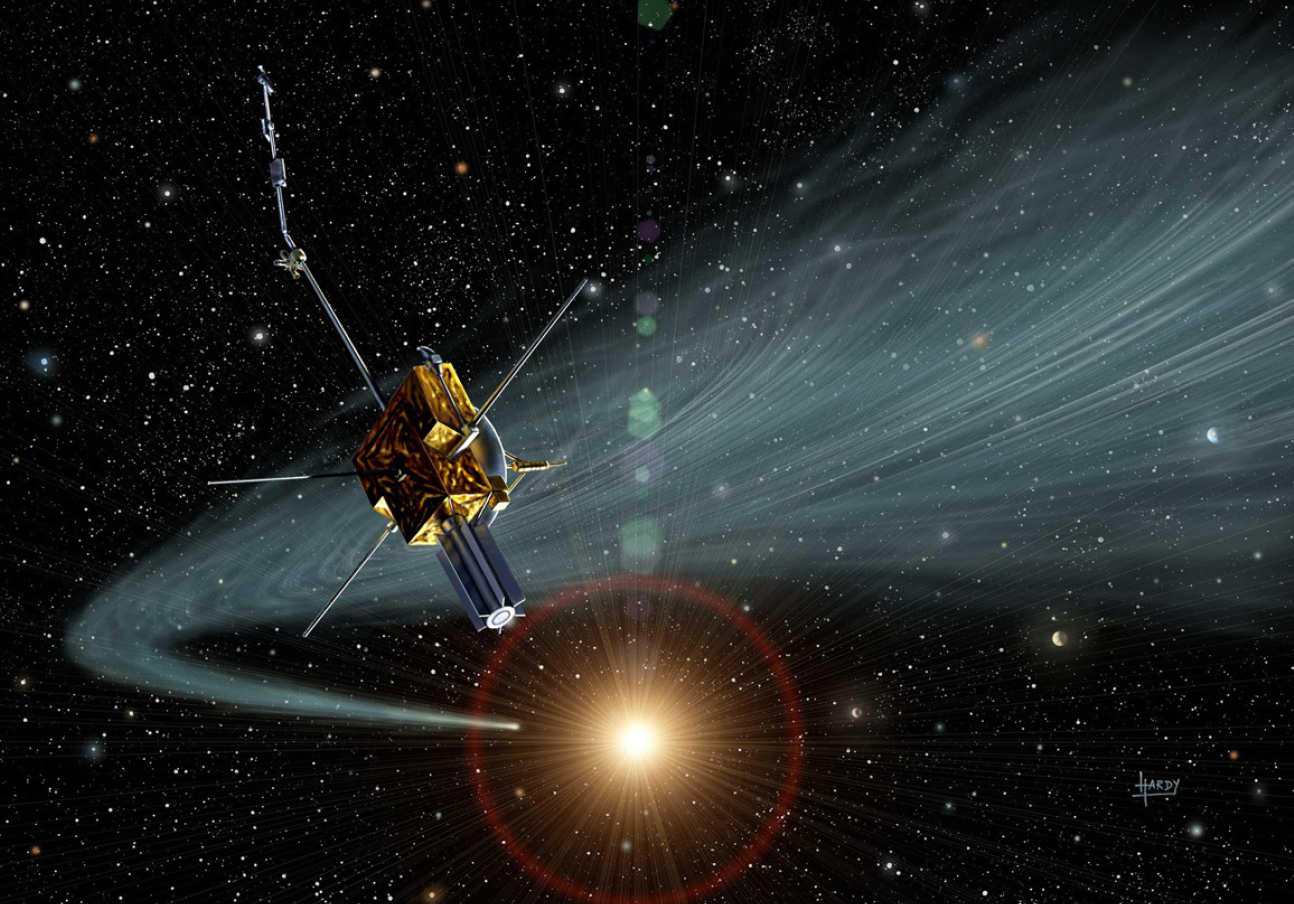

It has been a great mission, for several members of the Space and Atmospheric Sciences group a large fraction of their scientific career. Prior to the Ulysses mission, there was no heliospheric research in Britain, and this mission has produced now two generations of scientists who have become leading members of the worldwide community in this discipline. Image shows artist's imperssion of the discovery by Ulysses of comet Hayakutake's tail (Image by D. Hardy, ESA)

Despite all the expectations of the spacecraft operations team that the remaining fuel would have frozen by now, thus ending the mission, Ulysses has once again proved to be a great survivor and at the time of writing in late December 2008, all the signs are now that the spacecraft will continue to operate into 2009. Nigel Angold, the ESA mission operations manager says "Any estimate I make at this point about when the fuel will freeze or run out would be purely guesswork- the spacecraft has continued to surprise even the most optimistic among us. But it's beginning to look like those Ulysses 1990-2008 polo shirts were a little premature. At least they have "the Odyssey continues..." on the sleeve!". This unanticipated extra data is proving extremely useful in providing an additional out-of-ecliptic perspective on the present unusual solar minimum conditions in the heliosphere.

The 30 June 2009 was a major milestone in the group's history. The Ulysses spacecraft was finally sent the last command and was retired from active service after 18 years, 8 months and 24 days, or, in homogeneous units, 6842 days in orbit around the sun.

The roots of Ulysses in the group go back to the mid-70s; I have worked on it since early 1977. As the group evolved in the late 70s and early 80s, the Ulysses project was the rock on which we built our reputation as a leading hardware group in space sciences. It was launched on 6 October 1990, for a scheduled lifetime of 5 years. Ulysses outlived all the forecasts, but ran out of power (the half life of the plutonium 238 fuel in its radioactive thermoelectric generator is only 88 years; our RTG had in fact been loaded with Pu in the early 1980s). So there was no more power for its high-gain transmitter and for heating the spacecraft as it started out on its 4th trip out to Jupiter's orbit. This in turn threatened to freeze the hydrazine fuel needed for keeping the spacecraft pointed at Earth. The ESA/NASA Operations Team have worked wonders over the years to keep the spacecraft healthy, in the end they even prolonged the life of the spacecraft by an extra year, making all those T-shirts that were made last year (1990-2008) obsolete.

Recently, the data return dwindled from the usual 98% to less that 10%, with worse to come in the coming weeks as even the Deep Space Network's 70 m dishes struggled to catch a few bits per second from the distant spacecraft. So the decision was to terminate the mission; this was carried out yesterday from the Operations Control Room in JPL, Pasadena by setting the last command sequence to include a powering down of the spacecraft's transmitter.

It is, of course, the end of an era, but a magnificently successful one for solar and heliospheric science, as this unique mission, with its polar orbit around the sun, provided our only insight into the 3D nature of the sun's space environment. Ulysses enabled this research field to develop and flourish. For our group, with the leadership of the magnetic field investigation and a major share in the group of instruments that measured energetic solar particles and cosmic rays, Ulysses brought remarkable opportunities to take a world-leading role in heliospheric science. Group members have been involved in many hundreds of scientific publications, including in Nature and Science. A dozen and a half PhDs were based on the Ulysses data in the group. We can certainly be proud of what we have achieved with Ulysses. The data from Ulysses have been archived and will remain the hard evidence on which future theories of the solar wind and the heliosphere can be tested.

Of course many group members had been involved in Ulysses over the years, several remain whose scientific career has been helped by Ulysses. I would just like to evoke those names now who were involved from the early days with me and contributed to our instruments: Prof Harry Elliot (HoD until 1980, he gave his blessing to our involvement in Ulysses), Prof. Peter Hedgecock (first PI of the magnetometer, HoD until 1984), Prof Bob Hynds (who led a double life as Head of what was then the IC Computer Centre, but was also a very active instrument builder), and not least at all Trevor Beek, still present, who actually built most of our instrument hardware on Ulysses.