Raising the temperature of the UK heat pump market: Learning lessons from Finland

by Matthew Hannon

This blog is based upon a peer-reviewed paper available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421515002347

It wasn’t so long ago that the UK’s dependence on fossil fuels to provide heating services raised few eyebrows within government. This was during a time when climate change did not figure as a major political issue, the UK had secure control of healthy reserves of oil and gas in the North Sea and energy prices remained consistently low post-oil crisis. However, in the past decade this picture has changed dramatically. In 2004 the UK became a net importer of fossil fuels, in 2008 it introduced its Climate Change Act and between 2003 and 2013 it witnessed a ‘real’ doubling of its domestic energy prices. In the context of these developments heat has become a hot political topic in the UK, as evidenced by its recent 2013 strategy The future of heating: meeting the challenge.

In the context that in 2012 heat consumption within buildings accounted for 12% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) the UK government’s immediate focus is on how the decarbonisation of heat could help it meet its 4th carbon budget. Set in June 2011 the budget represents a legislated cap on the amount of greenhouse gases the UK can emit between 2023-2027, culminating in a 63% cut in GHGs by 2030 relative to 1990 levels. It is one of many budgets that will constitute critical ‘checkpoints’ on course to meeting the UK’s 2050 emissions reduction target of 80%.

A scheduled review of the budget in 2014 by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), an independent statutory body established to advise government on emissions targets, concluded there was no basis to change the budget. However, the review process resulted in an updated abatement scenario, which envisages a 38% reduction of building sector emissions by 2030 on 1990 levels, with heat making up the vast majority of this abatement. Crucially the deployment of 4.6 million heat pumps[1]by 2030, together producing 51TWh of renewable heat and accounting for 12% of the UK’s building heat consumption, is expected to play the leading role in this transition.

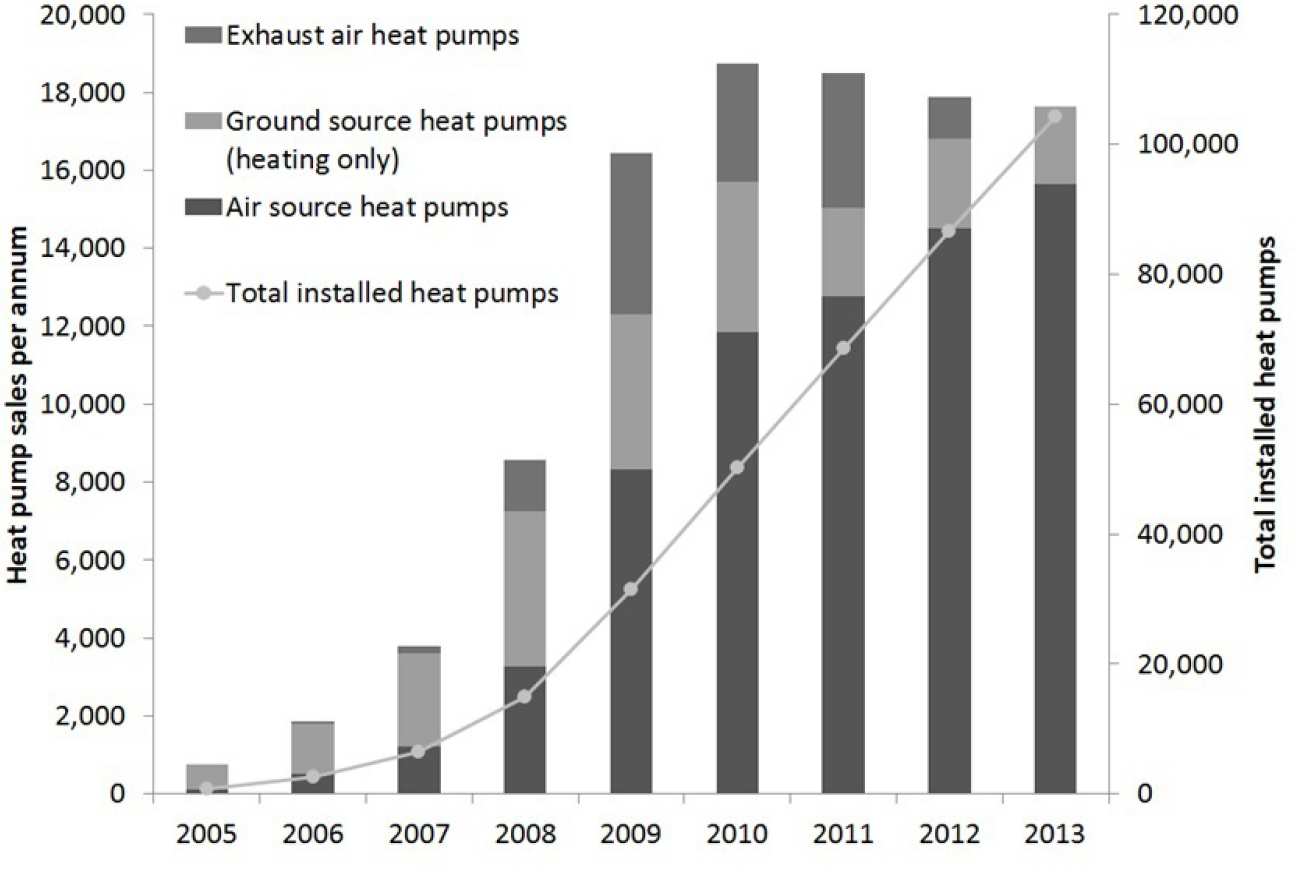

Realising this vision presents a major challenge considering that in 2013 only 104,000 heat pumps were operating in the UK, together producing 1TWh of renewable heat and accounting for only 0.2% of the UK’s building heat consumption. By 2030 both a factor 44 increase in the number of operational heat pumps and a factor 50 increase in the annual primary energy output these deliver is necessary to achieve this aim. However, the current rate of heat pump sales in the UK is insufficient to make-up this shortfall with sales between 2010-13 averaging 18,000 units per annum. Should this rate continue in the period up to 2030 only 400,000 units would be operational by 2030, less than 9% of the number envisaged by the CCC scenario. Instead annual sales would need to average 265,000 units, 15 times the current rate. This poses serious questions about how the UK will achieve this colossal task.

The UK could look to learn lessons from other countries, such as Finland, who have already achieved similar levels of deployment. In 2012 Finland was home to over half a million residential and commercial heat pumps, together producing 4.1 TWh of primary energy. It also ranked second in terms of sales andheat output per capita, as well as third in terms of heat pumps installed per capita. Crucially its level of heat pump penetration today is very similar to that envisaged in the CCC scenario for the UK 15 years from now, not least in terms of energy output per capita. Furthermore, it has only been since the early 2000s that Finland’s market really took off, seeing a 12 fold increase between 2003 and 2012 in the primary energy output from heat pumps (see figure below). Whilst some of the factors that are likely to have facilitated this growth cannot simply be replicated (e.g. cold climate, relatively small gas network) we suggest that some valuable lessons can still be learnt.

On balance Finland’s building stock is more suitable for heat pump installation than the UK as it is typically younger and larger, well suited to heat pumps that require high thermal energy performance standards to operate cost-effectively and often require plenty of space to install, especially ground source heat pumps. Whilst space is at a premium in the UK, stimulating new-build construction and ensuring these are built to high efficiency specifications could present one solution. The UK might learn from Finland’s National Building Code (SRMK) outlines stringent energy performance standards that account for the carbon intensity of the building’s heat supply and thus encourage low-carbon heating solutions. Retrofitting is also essential considering that approximately 80% of the UK’s building stock in 2050 is believed to have already been built and that heat pumps require buildings that possess high thermal performance and low-temperature heating systems. Again the UK could take Finland’s lead by providing tax-breaks for homeowners to undertake renovations or extensions.

Only 22,000 Finnish households are connected to mains gas and so heat pumps do not normally compete with gas fired solutions on a cost basis. In contrast, heat pumps are in direct competition with gas boilers in the UK with 23.2 million households served by gas-fired central heating. Introducing subsidies for heat pumps could improve their business case versus gas. Ideally a balance should be struck between subsidies that cover a combination of capital and operational to cover both initial and ongoing cost barriers. For example, combining aspects of the UK’s recently discontinued Renewable Heat Premium Payment (RHPP) and the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) that replaced it. Another option is for the UK to mirror Finland by introducing fossil fuel taxes that simultaneously raise subsidy funds and make gas heating less attractive to consumers. However, negative impact on both the fuel poor and the energy industry would need to considered first. Finally, the UK could reduce heat pump costs by increasing its spend on technological innovation. Finland again leads the way, ranked first in 2011 amongst 25 OECD countries in terms of public energy RD&D budget per GDP, with the UK languishing in 19th.

An alternative short-term strategy could be for the UK to focus its efforts on deploying heat pumps across the 3.6 million households without gas boilers, which are typically heated by comparatively expensive oil or electricity. Convincing a large number of these to adopt heat pumps could make a valuable contribution towards meeting the UK’s fourth carbon budget.

In summary if the UK government is serious about heat pumps playing a star role in decarbonising the UK’s heat supply and helping it meet its 4th carbon budget then it serious consideration needs to be given to the practicalities of convincing 1 in 8 homes to adopt heat pumps within 15 years’ time. A wide-scale shift away from gas boilers is unlikely to happen organically considering recent falls in gas prices and improvements in boiler efficiency. The UK government may need to look to other countries like Finland to understand how best to simultaneously make heat pumps more financially attractive and ensure that its housing stock is compatible with these devices. Such a commitment could really help to raise the temperature of the UK heat pump market and put the UK on course to meet its 4th carbon budget.

[1] These are devices that transfer heat from natural surroundings (e.g. air, water or ground), by reversing the natural flow of heat, to provide energy services (e.g. space heating, hot water).